Inside Out

Clicking on photo sets highlighted in blue shows them in 'Lightbox'(TM) Enjoy !

This page is to re-discover some old lost buildings and structures, to see what they were like inside and were used for. Some of them are still standing and where possible, interior shots are included.

St Georges Hall & the World's first air conditioning system

I was privileged and honoured last Saturday to be given a private tour, along with about 15 Liverpool University Engineering students by Dr Neil S Sturrock JP BEng PhD CEng FCIBSE MSLL MILP MEI and Chairman of the Heritage Group of the Chartered Institution of Building Services and a retired Senior Lecturer in Building Engineering studies at LJMU. Add to this he is the authority on Dr David Boswell Reid, inventor and implementer of the World's First Air Conditioning system which the St Georges Hall is undoubtedly built around.

To see some of these places again for the first time since the mid 1970s when my dad showed me around here when he was deputy foreman of the building was fantastic and emotional for me personally. Back then though neither I nor my dad realised the significance of the apparatus and contraptions about us and it's a good job really that nobody just came in and gutted the place not realising the relevance of it all as an historical piece of engineering.

Boswell Reid also implemented this system into the Houses of Parliament buildings as well as many others listed later. The clock tower of the HoP which contains the big ben bell is actually a flue/chimney and is one of two towers on the building. Depending on which way the wind was blowing one tower would be used for fresh air intake before being tempered and one for the outlet in a nutshell.

Here is a paper Neil put together for the Liverpool History Society and I will add photos of my own taken during the trip which was utterly absorbing throughout:

Dr David Boswell Reid (1805-1863) – Ventilator of St George’s Hall

Dr Reid’s importance in the success of St George’s Hall and the historic significance of what he termed ‘Systematic Ventilation’ in the world of comfort engineering has only really been appreciated in recent years. Indeed St George’s Hall has now been recognised as the World’s First Air-Conditioned Building and the pioneering work Reid did in the first half of the 19th Century has affected most of our lives ever since. This article will look at the influences on his early life which led to this interest in the proper control of ventilation and temperature and will touch on other significant buildings he was involved with as well as briefly describing his incredibly elaborate system in St George’s Hall. (I have omitted his early life biography at this point)

David Boswell Reid’s involvement with St George’s Hall

actually began some time before he was officially requested to advise on a

suitable method for its ‘warming and ventilation’. He had been approached by

the architect, Harvey Lonsdale Elmes, early in 1841 for advice, as Elmes later

reported to the Assize Courts Committee on 28th April 1841. In his report, in

which he gives an estimate of the total cost of ‘uniting St George’s Hall and

the Assize Courts in one building’, Elmes states that ‘........I am induced to

draw the attention of the Committee to the arrangements made by Dr Reid at the

Houses of Lords and Commons’.

At the Committee’s request, Reid then attended a meeting on

29th July 1841 and both he and Elmes submitted reports suggesting the way

forward in terms of the ventilation of the building. When Elmes was considering

the various possible arrangements of the Concert Hall Building (St George’s

Hall) and the Assize Courts Building in October 1840, he had also been asked to

consider how a further building, containing Daily Courts (ie Magistrates’

Courts) and a Bridewell, might form part of the grouping. Indeed two of his

proposed layouts show the Concert Hall building to the West (roughly where St

George’s Hall now stands) with the Assize Court building to the North (roughly

opposite the new extension to the Empire Theatre) and the Daily Courts building

behind the Assize Courts building (roughly on the triangle where the Wellington

Column and the Fountain now stand). As we know the two Committees then agreed

that they would adopt Elmes alternative plan which combined the two buildings

in one, however, it is clear from Elmes’ drawings, that he then adapted his

Assize Courts winning competition entry so that the proposed Daily Courts and

Bridewell building could use almost the same front elevation. A perspective

sketch by Elmes of the proposed ‘Forum’ shows the Daily Courts building with a

200 ft high ventilation tower incorporated in it. This tower was to carry all

the vitiated air and all the chimney smoke from both buildings. Elmes’ sketch

of this arrangement was used by Reid as the frontispiece in his book on

ventilation published in 1844.

|

| Elmes Forum perspective sketch |

The ventilation tower can be clearly seen in the distance and would have dominated the area. The building to the right, which was already in existence, was John Foster Junior’s neo-classical facade to Lime Street Station. Elmes makes a big thing, in his report to the Committee, of the fact that his combined building would have ‘no smoke on the outside or ugly cowled chimney pots which under the usual system of building is next to impossible to avoid’. His design allowed for all of the 110 chimney flues in the building to be brought down into the basement and for all of the smoke, along with the vitiated air, to be taken in tunnels and fed into the base of the tower where a furnace would burn continuously to propel all of the exhaust air and smoke into the atmosphere. The building had actually reached principal floor level in 1845 before the proposed Daily Court building was abandoned and it is great testament to the cooperation between Elmes and Reid that they were able to re-route the flues and vitiated air shafts without having any serious effect on the ventilation of the main spaces. New shafts were incorporated into the four corner angles of the Great Hall to accommodate foul air, with the smoke chimneys alongside. However, Reid mentions in his ‘Instruction Manual’ that some of the less important rooms, for example along the West elevation would have less satisfactory control than was originally planned.

Reid convinced the building committee that an unnecessary expense could be avoided if they accepted that his system was not designed so that every apartment could be served simultaneously. He argued that if either of the Courts was in use the Great Hall would not be, or, at least, it would not be crowded with people listening to a musical performance. His system was designed so that it could ventilate the Great Hall OR the Courts and/or the Small Concert Room, although, if the Great Hall was not in use ALL of the power could be applied to any single space. The flexibility built into the method of operation is exceptional in both its originality and its perspicacity. At the centre of the system are three main air supply chambers, one above the other. The simplest way to describe these is to say that the top and bottom ones have cold (fresh) air, and the middle one has heated air and the air streams could be mixed to give the desired supply temperature to each space although this description is not strictly correct because there are many different ways that the air could be sent and there are a number of cross-over ducts and additional fresh-air inlets. However, the basic principle is the same as in modern systems.

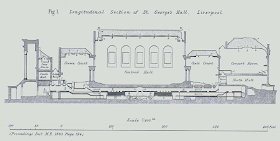

|

| Showing a section of the building showing the air distribution |

The Section clearly shows the positions of the North (right) and South ‘Fanners’ in the centre of the basement and the dark areas next to them indicate the Great North Water Apparatus and the Great South Water Apparatus (each consisting of 72

pipes, 4 in (100mm) diameter, the pipes being about 30 ft (9m) long). The arrows under the centre of the Great Hall (marked ‘Central Hall’ on the diagram) show the upper path of the cold (fresh) air. Below the main water heating coils are the additional fresh air routes for supply to the Small Concert Room (right) and the Grand Jury room (left). The ‘fanners’ were large paddle fans each with eight blades of 5 ft (1.5m) by 2ft 6in ((0.75m). the whole assembly being 10ft (3.0m) in diameter. They were driven by a 16hp steam engine. Additional ‘fanners’ were positioned in the East and West segments of the plant room and could be used to boost direct air supply or for recirculation by careful positioning of damper doors.

|

| The North fanner as seen from the position of the Steam Engine |

The edge of the Great North Water Apparatus can just be seen top right in the photograph, there was originally a door at that point (and on the left), which could be opened to allow air to pass between the hot pipes. The central ’Venetian Blind’ damper was operated by a lever from above and gave finer control over the rate of air flow. The water in the heating pipes was heated by two large, coke-fired, hot water boilers. There were two further hot-water coils at the bottom of the two vertical supply ducts for the Small Concert Room and another one under the South entrance. This latter one is now visible in the Heritage Centre. In addition to the hot water pipe coils there were 27 pipe coils heated by steam from two main, coke-fired, steam boilers but Reid was very insistent that the steam coils should only be used in extremely cold weather or for heating up the building before occupancy. He believed that passing air over such hot pipes had a deleterious effect on it. Reid was very aware of the effect of moisture level on comfort and he knew that warming air in Winter caused its Relative Humidity to be greatly reduced so he provided for steam to be directly injected into the air-stream. This steam was provided from a special, separate boiler near to the South Fanner. The steam to drive the steam-engine came from one of the main steam boilers, however, Reid’s Instruction Manual indicates that he anticipated that the system would function adequately most of the time without the steam-engine, or the fanners, having to operate. Indeed the steam-engine was removed, probably

early in the 20th Century, and the building functioned until 1984 without it. Ofourse, as with most of his other projects, Reid applied drawing power to the extract system by applying heat where necessary but with a building of this height it was relatively easy to provide a continuous throughput of air by taking it in at low level, heating it and then allowing it to escape at high level.

|

| Steam Injector Nozzles Under Great North Water Apparatus |

The East

portico of the building showing the fresh air inlet grilles either side of the

steps and around the edge, the underneath of the steps are hollow and forms the

undercroft where the air is tempered accordingly. Cooled during the summer or

warmed using hot water pipes in the summer.

The main air

intakes can be seen as dark rectangles near the top of the steps at each end of

the East Portico. The fresh air was washed by spray fountains under each grille

and then passed through the vast under-croft, where any dirt entrained in the

spray water would be deposited, on its way to the central distribution point.

Again Reid points out in his Instruction Manual that the under-croft, which is

about 30 ft(9m) high, would have the effect of cooling the air in Summer and

warming it in Winter, was this, perhaps, its main function?

The Undercroft referred to by Reid in his instruction manual

of how to work the system runs the whole length of East portico steps on St

Georges Plateau. On early drawings it is interesting to note that Lime st is

referred to as Victoria Way.

In all the major spaces, air is supplied at low level and

extracted at high level, following the natural path of warm air in a building.

This does mean that in Summer (when, in very hot weather, the Town Water Main

could be connected to the large heating coils) it would have been necessary to

apply power to keep the air moving in the same direction. Extract power was

originally applied to the four main vertical air extract shafts by means of

coke fires burning at the bottom of them in grates, however, the first

Superintendent, William McKenzie, soon realised that one of his assistants

spent most of his time caring for these four fires. He was constantly having to

carry coke to them and ashes away from them so McKenzie had fan-tail gas jets

installed at the base of each shaft and did away with Reid’s coke fires. The

same system had been employed in the base of the four combined chimney stacks,

into which all fireplace chimneys discharged, and these were also replaced by

gas jets and then eventually by electric fans. Control of this vast ‘pneumatic

machine’ (McKenzie’s phrase) was all done by hand but there was no ‘army of

workers’ as some writers have suggested. Indeed, apart from the building

Superintendent, William McKenzie there were only five men operating the heating

and ventilation system. There was one engineer in charge of the two steam

engines (the organ bellows were operated by a separate engine) who also

maintained the fans. There were two stokers who maintained the five boilers,

and there were two ‘labourers’, who operated the ventilation valves. The duties

of the labourers included helping the stokers when necessary.

|

| The steam engine mounting showing where the flywheel has worm away the stone on the left. |

The conical deflection plate above the steam engine

concentrated the escaping steam into a chimney and its upper surface forced the

air being driven by the fanners into the upper (cold) air ducts. There were

originally metal walls isolating the steam engine from the fanners.

|

| The transverse duct. |

Tempered air enters from the two sets of doors on the right.

At the far end of this duct can be seen part of the ‘East Concert Water

Apparatus’ at the base of the vertical duct serving the seating at the East

side of the Small Concert Room.

|

| The fantastic concert room showing air inlet grilles at floor level and in the stair risers. |

|

| The air outlet grilles in the ceiling of the Concert rooms. |

The main air outlets are in the rectangular ceiling panels

but the triangular grilles at the top of the wall could provide additional

extract. The four quadrant glass panels around the top of the chandelier (not

visible here) could be raised when the (gas) chandelier was lit to allow the

hot gases to escape.

|

| The open triangular outlet valve. |

And that's it from the paper, below are more

photos of my own .

|

| Part of the foundation structure and the undercroft |

|

| Just part of the complicated Great North water piping system. |

|

| More flues |

|

| Original light fitting |

Canvas flaps worked by ropes along lengths of ducting via pulleys. The walls are made of clinker, possibly produced at Cobbs quarry like those Eldon Street flats were in 1905.

|

| We're really in the bowels now but not a sign of a spider or a rat as we entered into rooms not very often used. |

|

| Another air collection chamber. We went under these low arches ducking into rooms no taller than 5 ft, one after the other with torchlight. |

|

| Arches inside arches. The bowels of St Georges Hall |

|

| St Georges Hall Concert Room |

|

| St Georges Hall. Parts the other beers cannot reach. Untouched parts for years with rusted off locks and trains from the underground which is right next door to us here can be heard. |

|

| These ducts run along the length of the hall in the roof void to help circulate the air. |

|

| This is the steel staircase that goes up and over the great hall ceiling, note the holes in the bricks of the ceiling visible through each gap in the stairs. |

|

| St Georges Hall air raid shelters (the bricked up doorway along the corridor wall) These are under the main steps at Lime street. |

THE ANN FOWLERS WOMEN'S HOSTEL

Originally built as a Welsh Chapel for the ever growing Welsh population in the Everton district, it was taken over as the Ann Fowler Women's Refuge Hostel for homeless and battered women with limited life skills. It stood on Netherfield Road South facing Upper Beau Street just North of Browside and the Everton lock up. It was discontinued for use in the late 1970s and fell into disrepair by a decade later, finally being demolished around 1990. The good work of Ann Fowlers continues as a Salvation Army organisation situated in a relatively newer building on Fraser Street off London Road and named The Ann Fowler Memorial Home.

This rooftop view over Everton from Scotland Road in 1925 shows the dominance of the twin pointed towers on the landscape. This was a building i'd often see and pass when attending nearby St. Gregory's school, Prince Edwin Street as well as knocking around with mates from the area and drinking in the Tugboat pub on Netherfield Road itself.

The sitting room, dormitory bedroom and sinks at Ann Fowlers as captured on 17th May 1910.

During the 1950s high rise housing was being built all around it as lengthy sloping streets disappeared. Other landmarks on Nethy including the Popular Cinema, The John Bagot Hospital and The Netherfield Conservative rooms were lost but still Ann Fowlers remained, only losing its towers pointed roofs.

An arson attack in the early 1980s saw the roof collapse with only the landmark shell intact. It was only a matter of time before the Corporation decided it was unsafe and a risk to the public.

|

A view from 1927 showing Ann Fowlers with houses running up

Browside, the viewing tower and the Everton lock up dating from 1787.

|

Originally built as a Welsh Chapel for the ever growing Welsh population in the Everton district, it was taken over as the Ann Fowler Women's Refuge Hostel for homeless and battered women with limited life skills. It stood on Netherfield Road South facing Upper Beau Street just North of Browside and the Everton lock up. It was discontinued for use in the late 1970s and fell into disrepair by a decade later, finally being demolished around 1990. The good work of Ann Fowlers continues as a Salvation Army organisation situated in a relatively newer building on Fraser Street off London Road and named The Ann Fowler Memorial Home.

This rooftop view over Everton from Scotland Road in 1925 shows the dominance of the twin pointed towers on the landscape. This was a building i'd often see and pass when attending nearby St. Gregory's school, Prince Edwin Street as well as knocking around with mates from the area and drinking in the Tugboat pub on Netherfield Road itself.

The sitting room, dormitory bedroom and sinks at Ann Fowlers as captured on 17th May 1910.

During the 1950s high rise housing was being built all around it as lengthy sloping streets disappeared. Other landmarks on Nethy including the Popular Cinema, The John Bagot Hospital and The Netherfield Conservative rooms were lost but still Ann Fowlers remained, only losing its towers pointed roofs.

An arson attack in the early 1980s saw the roof collapse with only the landmark shell intact. It was only a matter of time before the Corporation decided it was unsafe and a risk to the public.

DISUSED RAILWAY TUNNELS

As we left the daylight, delving deeper and deeper into the unknown, we could sense we were going uphill if only by the fact the arc of daylight we had left behind was getting smaller as it would if we were on an incline. We could hear seeping water from the arches above as our eyes became acustomed to the dark. One of us stumbled across a hole in the floor, whereupon a small stone was dropped into it, the sound of it hitting water some seconds later. Hell, we thought, that could have been one of us down there and decided not to go off alone but that didn't stop me at the back launching a stone up ahead onto the side wall, unbeknown to the leader who stopped, startled in his tracks.

Eventually we saw up ahead a square block of daylight coming in from above and decided it might be a way out and proceeded towards it. When we arrived there, we were amazed to see old mattresses, bicycle frames, rags, rusty prams, overgrown weeds, torn old newspapers and magazines, bits of wood and every other type of litter and rubbish you could image which must have accumulated over the years.

Upon focusing our eyes to the heavens above, we were further amazed and somewhat comforted to see somewhere we recognised. Those tenements above are Fontenoy Gardens we said. The walls were sheer with plants growing out of them, dank, damp and water stained, we could see there was no way out. We decided after threading carefully to press on ahead and soon we were lost in the darkness again but saw a vertical shaft of light beaming down up ahead, the type of which reminded me of a 'beam me up scottie' type cylindrical shape from Star Trek.

Arriving at it, we looked up a circular shaft like chimney to see clouds passing over it ahead, but again, no way up. Time was getting on now and we guessed we'd been down there an hour or so, bearing in mind the larking about en route. Furthermore, we could see no further light up ahead, only pitch blackness so decided to bottle it and retrace our previously safe footsteps.

Back on the surface and at home, I studied an A-Z to find we had walked part of the Waterloo railway tunnel and we'd gone under landmarks well known to us such as Byrom Street Polytech. The circular shaft of light was still a mystery and we thought it might have been somewhere within the walled garden to the rear of Christian Street library but after scaling its wall, we found that not to be. Trying to follow the line we took underground, we decided to trace it overland then there it was, the chimney is still there to this day on Wilde Street off Norton Street.

The shaft would have been used for the dispersion of steam from the puffing billy type railway engines and if we'd have walked its full length, we would have emerged at Edge Hill station after first coming across at least one other shaft which is in the grounds of Archbishop Blanch school. In days gone by, a winding mechanism was used for pulling these trains uphill to the large void that Fontenoy Gardens overlooked and is regarded to be Hodson Street catch area for runaway trains and in fact a railway worker was killed there in the past when hit by a goods wagon. Steam locomotives were used from Hodson Street to Edge Hill.

The part of the tunnel from what was Waterloo dock goods yard at Great Howard Street to Byrom Street is Waterloo Tunnel but the stretch thereonin to Edge Hill sidings is actually called Victoria Tunnel. Waterloo Goods yard was where Toys R Us and Costco are now situated. There is a tunnel which also runs from Edge Hill to Wapping goods station on the south dock road, called Wapping Tunnel which has shafts including ones at Cornwallis Street and Great George Street.

Upon investigating the history of where we'd explored, I found that Wapping tunnel opened in 1829, Waterloo Tunnel in 1849 - both were closed in 1972 Waterloo tunnel has a brick sewer running beneath it, possibly where we heard the stone mentioned earlier go plop. The duct would also have been used to house the winding cables used to pull the wagons up the steep gradient.

Eventually we saw up ahead a square block of daylight coming in from above and decided it might be a way out and proceeded towards it. When we arrived there, we were amazed to see old mattresses, bicycle frames, rags, rusty prams, overgrown weeds, torn old newspapers and magazines, bits of wood and every other type of litter and rubbish you could image which must have accumulated over the years.

Upon focusing our eyes to the heavens above, we were further amazed and somewhat comforted to see somewhere we recognised. Those tenements above are Fontenoy Gardens we said. The walls were sheer with plants growing out of them, dank, damp and water stained, we could see there was no way out. We decided after threading carefully to press on ahead and soon we were lost in the darkness again but saw a vertical shaft of light beaming down up ahead, the type of which reminded me of a 'beam me up scottie' type cylindrical shape from Star Trek.

Arriving at it, we looked up a circular shaft like chimney to see clouds passing over it ahead, but again, no way up. Time was getting on now and we guessed we'd been down there an hour or so, bearing in mind the larking about en route. Furthermore, we could see no further light up ahead, only pitch blackness so decided to bottle it and retrace our previously safe footsteps.

Back on the surface and at home, I studied an A-Z to find we had walked part of the Waterloo railway tunnel and we'd gone under landmarks well known to us such as Byrom Street Polytech. The circular shaft of light was still a mystery and we thought it might have been somewhere within the walled garden to the rear of Christian Street library but after scaling its wall, we found that not to be. Trying to follow the line we took underground, we decided to trace it overland then there it was, the chimney is still there to this day on Wilde Street off Norton Street.

The shaft would have been used for the dispersion of steam from the puffing billy type railway engines and if we'd have walked its full length, we would have emerged at Edge Hill station after first coming across at least one other shaft which is in the grounds of Archbishop Blanch school. In days gone by, a winding mechanism was used for pulling these trains uphill to the large void that Fontenoy Gardens overlooked and is regarded to be Hodson Street catch area for runaway trains and in fact a railway worker was killed there in the past when hit by a goods wagon. Steam locomotives were used from Hodson Street to Edge Hill.

The part of the tunnel from what was Waterloo dock goods yard at Great Howard Street to Byrom Street is Waterloo Tunnel but the stretch thereonin to Edge Hill sidings is actually called Victoria Tunnel. Waterloo Goods yard was where Toys R Us and Costco are now situated. There is a tunnel which also runs from Edge Hill to Wapping goods station on the south dock road, called Wapping Tunnel which has shafts including ones at Cornwallis Street and Great George Street.

Upon investigating the history of where we'd explored, I found that Wapping tunnel opened in 1829, Waterloo Tunnel in 1849 - both were closed in 1972 Waterloo tunnel has a brick sewer running beneath it, possibly where we heard the stone mentioned earlier go plop. The duct would also have been used to house the winding cables used to pull the wagons up the steep gradient.

Waterloo Goods Yard at the Western end of the Victoria/Waterloo tunnel. It was expanded to take passengers across the dock road and into Riverside Station at one point.

Waterloo Tunnel in use in 1971, a year later, it would be closed and still is. Pic with thanks to Keith Rose.

The deep cutting seen here is where we looked up and saw Fontenoy Gardens, the nearest block which this photograph of Joe Devine's was taken from. This is the smaller block, Great Crosshall Street end of the development which was above the careers office.

The deep cutting seen here is where we looked up and saw Fontenoy Gardens, the nearest block which this photograph of Joe Devine's was taken from. This is the smaller block, Great Crosshall Street end of the development which was above the careers office.

Everything but the kitchen sink confronted us, though there is a bath there. A window frame, pallets, a bedstead and a living room chair make up some of the rest of what's been discarded over the years. Bellamy and Attenborough would have been made up with the plant wildlfe too

Fontenoy Gardens in the late 1980s just before and during demolition as captured by Ron Formby and Freddy O'Connor respectively. The little street which runs between the cuttings is Hodson Street and is now incorporated into one of the back gardens of the houses built in this site. As the tunnel runs Eastwards towards Edge Hill, so it is named Victoria Tunnel and Steam loco's were used to move the goods trains, hence the need for ventilation shafts at regular intervals from that point on. When built, these tunnels had to navigate under two burial grounds on Hunter Street, one being the Quaker Friends meeting house and the other, Christ Church graveyard.

Two fascinating photos from one of our urban explorer friends on the 28days website and forum namely, Earth worm Jim and Dav.P. The left one is Waterloo tunnel with the railway line sleeper marks still evident. This tunnel looks more curved from ground level than the Wapping tunnel on the right which seems to rise as sheer before curving at a much taller height.

Upon my return to pastures old in October 2009, much of the rubbish had been removed from the cutting as studies were made into the feasibility of the tunnels being re-opened to goods traffic to relieve the roads above.

MILL ROAD MATERNITY HOSPITAL

Many

Northern Liverpudlian's lives started at Mill Road Maternity Hospital off West

Derby Road. I know that a few generations of my own family's did including my

grandparents, parents, myself, brother, wife, in-laws and then my own children.

There is even a facebook page dedicated to its services in this role so here is

the history of it. Overview:

Mill Road

Hospital was built by the West Derby Union Board of Guardians as a workhouse

for the sick poor. By 1891 it had been renamed Mill Road Infirmary. It remained

a general hospital until the Second World War. The only major addition to the

original institution was a new outpatients department which was built in 1938.

During the

Second World War the hospital was very badly damaged by air raids. In 1941

patients had to be transferred to Broadgreen Hospital where 610 beds were made

available for Mill Road patients. Fortunately the new outpatient block was not

damaged. When the war ended there was a debate about whether or not the

hospital should be rebuilt. When it did finally reopen in June 1947, it was not

as a general hospital but as a specialist maternity hospital. In November 1993

the main part of the hospital was closed. Eventually the hospital was replaced

by a larger maternity hospital in Toxteth, which opened in 1995: the new

Liverpool Women's Hospital. From workhouse to Mill Road hospital

Looking

after the poor.

Like many

hospitals across the country, Mill Road hospital grew out of the need to

provide workhouses because of the changes made by the New Poor Law of 1834. The

West Derby Union was formed as a result in 1837 to oversee the poor of the

parishes which stretched from Garston in the south to Ince Blundell in the

north. The Guardians of the new Union purchased land in Mill Lane to build the

West Derby Union Workhouse. After inmates from the old Poor House were

transferred there and others from Brownlow Hill workhouse moved in under a

rental arrangement with the Liverpool Select Vestry, it was soon realised that

the new workhouse at Mill Road was too small. All sick inmates were sent to a

fever hospital and the fever sheds converted into workshops.

The problem

of caring for the sick poor was helped when a new hospital was built in 1852 on

West Derby Road between Horne Street and Hygeia Street. At that time, nurses

were not trained. They were often illiterate and worked on mainly domestic

duties. Cases of dismissal for drunkenness or fighting were not uncommon.

By 1862 the

issue of looking after the able-bodied poor and the sick poor was becoming a

problem. It was decided to purchase thirty-seven acres at Walton-on-the Hill

for a new workhouse. The Board of Guardians intended to sell both the hospital

at West Derby Road and the Workhouse at Mill Road to pay for the new venture.

But once again the need for accommodation had been underestimated and it was

realised that the new Walton workhouse would not be big enough. What had been

Mill Road Workhouse was kept and became a workhouse hospital for the sick poor.

The decision

was not popular with the local residents who had been led to believe that the

threat of contagious diseases was to be removed with the transfer of patients.

Despite a number of protests, the workhouse hospital at Mill Road remained.

The grand layout of the workhouse and soon to be hospital. Here, we see the Operating Department in 1925.

The New

Infirmary

The threat

of disease caused by unsanitary conditions together with an inadequate and

outdated building, led to the decision to rebuild the workhouse hospital. In

March 1891 work started on the Mill Road Infirmary on what had been the site of

the workhouse for the sick poor. The cost of the 700-bed building was estimated

at £100,000 (just over £6 million at 2002 values). Nurses were relocated at new

premises across the road to provide additional space. The last patients were

transferred from their temporary accommodation at Belmont Road in 1895.

Treatment of

the mentally ill was also carried out at Mill Road. The Lower Hospital was a detached

block on the Mill Road site and inmates there became knows as ‘lowers’. Often

troublesome patients were transferred to the Lower block with little knowledge

of their true condition. It was simple procedure requiring no legal obligations

Before the First

World War (1914-1918), Mill Road started to take in paying patients and certain

parts of the hospital were used just for this purpose. The strain on voluntary

hospitals meant that alternative accommodation was needed. This mixed use

served an important part in decreasing the divide between the two types of

hospital. Despite the change of name, the institution would still be known as

the workhouse hospital for many years.

1925 was an

important year for the hospital. The General Nursing Council recognised it as a

Training School for Nurses a new wing for the departments of Operating, X-Ray

and Electro-therapeutics was opened and Neville Chamberlain, the Minister for

Health, paid a visit. In 1937 a new Superintendent Dr Leonard Findlay was

appointed. He was a popular figure and with his enthusiasm and direction, Mill

Road gained a reputation as the best pre-war hospital for post-graduate study

in Liverpool. Mill Road hospital and the Second World War

Mill Road

hospital in Liverpool was busy during the Second World War (1939-1945). For

example on 14 September 1939 an accidental explosion at the docks brought in

eighty patients and it became obvious that the hospital was under-prepared for

casualties of war. Action such as transferring patients to suburban hospitals

was taken to ensure that the hospital could cope. Heavy air raids were

experienced in Liverpool during March 1941 and continued until the first week

in May when the worst attacks of all occurred.

On 3 May

1941 the hospital itself was hit. Eighty-three people were killed that night

including seventeen members of staff. Twenty-seven people (of which seventeen

were staff) were injured. The four hundred or so surviving patients were

transferred to other hospitals. Three ward blocks were totally destroyed and

the in-patient area was not fit for use.

The blitz devastated part of the infirmary but you would never have known it when visiting there in later decades.

Mill Road

hospital and the National Health Service

When the

National Health Service (NHS) was set up in the United Kingdom in 1948, the

administration of Mill Road infirmary passed from Liverpool Corporation to the

Eastern Hospitals Board. It had not been used at all after the wartime bombing

and staff went to work at Walton and later Broadgreen hospitals.

After the

war it was decided to salvage and make good what was left of Mill Road and to

turn it into a hospital that specialised in obstetrics (child-birth) and

gynaecology (problems only affecting women). Mill Road Maternity Unit was

opened on 5 June 1947 at the hospital and was one of many maternity hospitals

which had to cope with the post-war baby boom and the increase in the number of

births. In 1950 the Obstetrical Flying Unit (later run in partnership with

Liverpool Maternity Hospital) was introduced. A squad of specialists could be

used to attend difficult home births. Improvements during the mid-1950s

included additional isolation accommodation, facilities for sick antenatal

patients, a residential section for medical students and a new premature baby unit.

The

artificial limb and appliance centre.

A dedicated

artificial limb and appliance centre, the first in the country, was built at

the Mill Road site and opened on 25 July 1961. It served the entire Liverpool

Regional Health Board area with a population of two and a half million and

supplied prosthetic aids to National Health Service patients and war

pensioners.

Administrative

changes and the end of an era.

Changes

within the NHS in the mid 1970s almost saw the closure of Mill Road as

cost-cutting measures were called for by Liverpool Area Health Authority. A

compromise was found where Mill Road was to stay open, taking on the maternity

units of Broadgreen and Sefton General. The 1970s and 1980s saw many

administrative changes. In 1985 Mill Road, Liverpool Maternity Hospital and the

Women’s Hospital came together as the Liverpool Obstetric and Gynaecological

Unit. The Unit became a trust status in 1992 and became the Liverpool Obstetric

and Gynaecological Service NHS Trust. A new building was needed and in 1992

work started on the New & United Liverpool Women’s Hospital building at

Crown Street. In-patient services were transferred from Mill Road to the

Women’s Hospital in November 1993. By 1995 Mill Road was completely closed for

business and the building was demolished. Some eminent Mill Road hospital

staff.

Robert Atlay

was the Medical Director at Mill Road hospital in Liverpool when it finally

closed its doors to patients in 1993. He had fought to keep the hospital open

in the 1970s and 1980s when cuts were being made and he is credited with many

administrative reforms which made the maternity unit a happy place to visit. He

had studied at Mill Road as a student in 1958 and spent most of his career

there.

Leonard

Findlay was appointed as Superintendent in 1937 and was one of the reasons why

Mill Road got a reputation as the best pre-Second World War hospital for

post-graduate study in Liverpool. He received the George Medal for bravery

during the German air raids on the city in May 1941 (the 'blitz').

P.W.M.L.

Langley was a twenty-three year old Senior Resident House Surgeon who died of

typhoid in 1880. He is remembered by a plaque which is now at the New &

United Liverpool Women’s Hospital.

John

Birkbeck Nevins was one of the long-standing medical figures at the hospital. A

graduate of Guy’s Hospital London University, he practised at Mill Road from

1847 to 1863. He went on to provide a report which was used to put together the

Contagious Diseases Act of 1846 and 1866.

Mr Nathan

Raw was a Medical Superintendent who started in 1896. He went on to serve on national

and international committees concerned with tuberculosis and psychiatry. During

the First World War he was senior physician of the Liverpool Mobile Base, a

mobile unit that followed the troops at the firing line. He pioneered the use

of anti-toxins in infective diseases and the use of x-ray diagnosis, finally

giving up work due to the effects of irradiation to his hands.

Gertrude

Riding started work at Mill Road in 1910. She was Matron from 1927 until she

retired in 1948. She lost an eye as the result of injuries during the blitz.

She was a founding member of the Royal College of Nursing and was awarded the

Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.) for her services during the war.

Some pictures with thanks to L.E. Thomas as the hospital sees out it's final few years of life before its eventual closure and demolition.

SEAMAN'S ORPHANAGE

In April 1870, Liverpool City Council donated a plot of land in the North East of Newsham Park for an orphanage. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse, on the 11th September 1871, the foundation stone was laid by Ralph Brocklebank and within a few months £8,000 had been raised for the building. In January 1874, 114 children moved into the orphanage and it was officially opened on 30th September 1874 by Queen Victoria's fourth son the Duke of Edinburgh.

On 12th May 1886, Queen Victoria visited The Seamen's Orphanage accompanied by the Duke of Connaught and Princess Beatrice. Queen Victoria agreed to become patron of the orphanage with Princess Mary and as a result it was granted the title 'Royal'.

At the start of World War Two, preparations were made for the children at The Seamen's Orphanage to be evacuated. This took place on the 11th September 1939, exactly 68 years after the foundation stone was laid.

Liverpool Seamen's Orphan Institution.

After the Second World War in 1948, there were only 130 children left in the orphanage. The introduction of Family Allowance and the launch of the National Health Service enabled families to care for children in their own home. On 25th July 1949, it was decided that the orphanage should close down and two days later the doors finally shut with many of its children being sent to boarding schools.

In 1951, the Ministry of Health bought the building and turned it into Park Hospital, however, this closed down in 1988 and the building is currently not in use.

On 12th May 1886, Queen Victoria visited The Seamen's Orphanage accompanied by the Duke of Connaught and Princess Beatrice. Queen Victoria agreed to become patron of the orphanage with Princess Mary and as a result it was granted the title 'Royal'.

At the start of World War Two, preparations were made for the children at The Seamen's Orphanage to be evacuated. This took place on the 11th September 1939, exactly 68 years after the foundation stone was laid.

Liverpool Seamen's Orphan Institution.

After the Second World War in 1948, there were only 130 children left in the orphanage. The introduction of Family Allowance and the launch of the National Health Service enabled families to care for children in their own home. On 25th July 1949, it was decided that the orphanage should close down and two days later the doors finally shut with many of its children being sent to boarding schools.

In 1951, the Ministry of Health bought the building and turned it into Park Hospital, however, this closed down in 1988 and the building is currently not in use.

Two photographs from 1895 taken on Orphan Drive, Newsham Park. The first shows the chapel, now demolished for a health centre, the second shows the main building which as you will see, some 115 years later, we managed to gain access to explore.

The grand foyer, a classroom and a dorm as pictured in 1895

The dining hall and sitting room in 1895.

Orphans uniforms and orphaned boys and girls.

Some links: Life in the Orphanage by Phyllis Gilmore

Boot making in the bespoke workshop and woodwork classes in 1895 too.

Left: One of the wards in the building.

Right: Playtime, 1912 style.

And so it was with thanks to our friend Johnny Blue that on a cracking Saturday morning the 17th April 2010, four of us with an historical interest in Liverpool gained access to the old Seaman's Orphanage which had served the latter part of its life as Park Hospital. It was a privilege to walk in the very same footsteps of so much history attached to this building.

A Welcome sign is embedded into the fantastic tiled floor in the entrance hall. Old metal radiators still adorn the walls which are lined with gothic style windows. That theme is continued with pointed arch corridors running the length of the main hall. The last pic shows the lift, electricity still running in a small part of the building.

An original balcony over the dining room shown in the 1895 pictures above, complete with 1960s light fittings. Fancy plasterwork, friezes and beams are spoilt only by the flaking paint from years of neglect. False ceiling panels now leave the real height of the room to the imagination but it wasn't difficult to picture the vastness and the large furniture that once would have graced the v dining hall and dormitories. More vertical narrow windows serve one of the many small side rooms as my fellow explorers capture some of the scenes on video camera.

The reception area from when the building was used as a hospital complete with some fitted furniture including wardrobes, chest of drawers, mirrors and curtains. Notice the ornate fireplace and hearth.

The stairwell and safety guards with original newel posts. It was strange to think of all the people that had trodden these very boards and steps. If ever a building would have ghosts of the past, this would be it but there was not a bad feeling in the place.

Corridors off rooms off rooms off corridors. Boarded up windows letting in shards of April sunshine. A pristine but bare bathroom that has stood unused for over 2 decades.

The other side of the reception window still houses bookcases and office furniture like time stood still but stock shelves are almost bare but for flash floor cleaner.

A zonal floor plan of the intricate alarm system which has made the plan vandal proof even to this day. Next, we ascend the narrow stone circular staircase to the top of the belfry.

The narrow doorways leading to the stone stairway. Cast iron drainage pipes even exists within the building and arachnophobia is a no no at this level as this foot square cobweb confirms. A fine setting for a horror movie.

Roof trusses at the uppermost portion of the building and some slipped tiles revealing daylight which sadly means a number of tubs having to collect rainwater which lets in. From this height, we get a good view of the rooftops.

Some of the amazing outbuildings and annexes that cannot be seen from the main road at Orphan Drive. Above the doorway of the building on the left is a relief sculpture of a child sat on a coiled rope whilst cradling a ship. A bygone reminder of the building's original use. An ornamental balcony and stone planters complete the facade. On the right, workshops which housed some of the lessons as seen on the 1895 photographs.

You can get a good view of Newsham Park and the grounds and gardens as well as the roof line from the belfry windows. Little garrets adorn these areas and the chimney stack ornamentation is impressive.

The rear of the orphanage with its ancillary buildings.

The colourful gardens and the master gates which lead to double wooden doors through which horse drawn carriages of seamen's orphans would have been transported to their new home. Later of course, it was used for ambulances bringing the sick to Park Hospital. The last photograph shows the intricate detailing of the cast iron downspouts and rainwater channels from the ornamental balcony above the bay window.

ARDEN HOUSE SALVATION ARMY HOSTEL

At the end of the 1800s, it was established that accommodation was required for the floating population of labourers and dockers in the Scotland Road area. Many hundreds could be seeking lodgings each night and one attempt at solving this problem was the opening of the Bevington Bush People's home by Liverpool People's Homes Ltd. The foundation stone was laid on 21st June 1898 by Thomas H. Ismay and it was opened by the Earl of Derby on 11th January 1900. This building offered 500 sleeping rooms, which were wonderfully clean and cheerful. They were for the sober working man, there being no admittance for the habitual drinker.

The building was requisitioned by the admiralty during WWII in November 1941 and was sold to the Salvation Army in November 1945 as a hostel for the destitute and homeless and renamed Arden House, it had a bridge that connected two parts of the building which straddled Arden Street. It was also used by passing lorry drivers as an overnight stay, the waste ground alongside the hostel being a perfect parking spot for all manner of transport vehicles during the 1960s and 70s, the thirteen shillings fee being some three shillings below the usual going rate. Having stood just off Scotland Road for nearly 9 decades, it became disused and lay empty during the 1980s, finally being demolished in 1990.

The building was requisitioned by the admiralty during WWII in November 1941 and was sold to the Salvation Army in November 1945 as a hostel for the destitute and homeless and renamed Arden House, it had a bridge that connected two parts of the building which straddled Arden Street. It was also used by passing lorry drivers as an overnight stay, the waste ground alongside the hostel being a perfect parking spot for all manner of transport vehicles during the 1960s and 70s, the thirteen shillings fee being some three shillings below the usual going rate. Having stood just off Scotland Road for nearly 9 decades, it became disused and lay empty during the 1980s, finally being demolished in 1990.

Arden House in the 1960s, first from Blackstock Street as captured by Bernard Fallon and the showing the connecting bridge over Arden Street from Bevington Bush.

Arden House from various angles in the 1980s, some of them showing its near neighbour, the Wellington public house. The pic bottom left was captured just after a snowfall and the one bottom right is during demolition.

Bevington

Bush and indeed the very hostel above is outside where Jamaican street

performer Seth Davy is said to have performed with his set of dancing

marionette dolls around the late 1890s and early 1900s. A song lamenting his

death in 1904 known as 'Whisky on a Sunday' and also as 'The Ballad of Seth

Davy' was written by Glyn Hughes (1932–1972), and became popular during the

second British folk revival. Whisky on a Sunday - original lyrics.

He sits in

the corner of old beggar's bush, On top of an old packing crate,

he has three

wooden dolls that can dance and can sing, And he croons with a smile on his

face.

Come day, go

day. Wish in my heart it was Sunday,

Drinking

buttermilk thru the week - Whisky on a Sunday.

His tired

old hands tug away at the strings, and the puppets dance up and down,

A far better

show than you ever would see, In the fanciest theatre in town.

Come day, go

day. Wish in my heart it was Sunday,

Drinking

buttermilk thru the week - Whisky on a Sunday.

In nineteen

o four, old Seth Davy died, and his singing was heard no more,

His puppets

and string they were thrown in the bin, and his board went to mend a back door.

Come day, go

day. Wish in my heart it was Sunday,

Drinking

buttermilk thru the week - Whisky on a Sunday.

But on

stormy nights, when you're passing that way, and the wind's blowing up from the

sea,

You'll still

hear the songs of that old Seth Davy, as he croons to his dancing dolls three.

Come day, go

day. Wish in my heart it was Sunday,

Drinking

buttermilk thru the week - Whisky on a Sunday. And the lyrics with a Liverpool

slant to them.......

SETH DAVY.,

by Glyn Hughes.

He sat on

the corner of Bevington Bush, astride an old packing case,

And the

dolls on the end of the plank went dancing, as he crooned with a smile on his

face.

CHORUS:

"Come day, go day. Wishing me heart for Sunday.

Drinking

buttermilk all the week; whisky on a Sunday."

2; His tired

old hands drummed the wooden plank, and the puppet dolls they danced the gear.

A far better

show then you ever would see, at the Pivvy or new Brightion Pier.

CHORUS; Come

day go day........

3; But in

nineteen o'four old Seth Davy died, and his song was heard no more.

And the

three dancing dolls ended up in a bin, and the plank went to mend a back-door.

CHORUS:"Come

day, go day

4; But on

some stormy nights, down Scotty Road way, when the wind blows up from the sea,

You can

still hear the song of old Seth Davy, that he sang to his dancing dolls three;

CHORUS;

"Come day, go day...

SOME DISUSED CINEMAS

Former Derby Cinema, Liverpool - Photographed Oct 09

This forgotten building on Scotland Road has an interesting history.

Built as a Methodist Church in 1843, it was extended in 1865 and became a cinema in 1912 whereupon the front was extended for the foyer and projection room. A wider extension was added to the rear in 1929. It survived as the Derby until 14 May 1960 when it was converted to Whitneys car showroom with a large picture window added to the ground floor frontage. At this point the balcony and stairs were removed and the upstairs was sealed up. It was Coynes funeral directors in the 1980s and 90s before lying lay derelict until in 2009, a fireworks retailers took over residence.

Removal of the false ceiling has revealed the proscenium, the curved 1929 ceiling and the 1865 church ceiling as well. The cellars contain a large mouldering oil boiler, the heating pipes (car showroom) are visible in the auditorium shots. Access was gained, with much difficulty, to the sealed off portion. It was an eerie feeling to be the first person to walk up the projection room steps in 48 years! Everything had a thick layer of dust and was in darkness, due to the cladding. A sample of the film on the floor is shown, preserved by the cold, dry atmosphere.

This forgotten building on Scotland Road has an interesting history.

Built as a Methodist Church in 1843, it was extended in 1865 and became a cinema in 1912 whereupon the front was extended for the foyer and projection room. A wider extension was added to the rear in 1929. It survived as the Derby until 14 May 1960 when it was converted to Whitneys car showroom with a large picture window added to the ground floor frontage. At this point the balcony and stairs were removed and the upstairs was sealed up. It was Coynes funeral directors in the 1980s and 90s before lying lay derelict until in 2009, a fireworks retailers took over residence.

Removal of the false ceiling has revealed the proscenium, the curved 1929 ceiling and the 1865 church ceiling as well. The cellars contain a large mouldering oil boiler, the heating pipes (car showroom) are visible in the auditorium shots. Access was gained, with much difficulty, to the sealed off portion. It was an eerie feeling to be the first person to walk up the projection room steps in 48 years! Everything had a thick layer of dust and was in darkness, due to the cladding. A sample of the film on the floor is shown, preserved by the cold, dry atmosphere.

Former Royal Cinema, Breck Road, Liverpool - Photographed Oct 09

This was originally the Theatre Royal, opened in 1888. Converted to a cinema in 1920, it closed in January 1965. Used as a "Top Flight" bingo hall until the 1980's, it is presently a furniture shop.

Above the false ceiling are relics of its past. The structure is in bad condition but the pigeons are the greatest hazard, after rotten floors. Planning has been granted to replace it with flats! Essoldo were the last cinema operators, leaving most of the vintage electrical equipment behind. The motor generator sets were never replaced, lasting its entire cinema life!

This was originally the Theatre Royal, opened in 1888. Converted to a cinema in 1920, it closed in January 1965. Used as a "Top Flight" bingo hall until the 1980's, it is presently a furniture shop.

Above the false ceiling are relics of its past. The structure is in bad condition but the pigeons are the greatest hazard, after rotten floors. Planning has been granted to replace it with flats! Essoldo were the last cinema operators, leaving most of the vintage electrical equipment behind. The motor generator sets were never replaced, lasting its entire cinema life!

The Princess Cinema on the Selwyn Street/Brewster Street junction in Kirkdale opened on 11th May 1931 housing 1,460 seats, all on the one level.

The architect was G. Stanley Lewis and it was taken over by Essoldo in 1958 before closing on 22nd October 1966 then used as a bingo hall for the next 34 years. It has been disused for some time now and sadly awaits demolition.

The architect was G. Stanley Lewis and it was taken over by Essoldo in 1958 before closing on 22nd October 1966 then used as a bingo hall for the next 34 years. It has been disused for some time now and sadly awaits demolition.

VULCAN STUDIOS WATERLOO ROAD

Vulcan Studios was first established in the denim days of the eighties, providing space and time for artists and musicians to struggle through their formative years. Barry, not a musician just a hippy having hitched his way around the world, settled back in Liverpool with his wife and child. Having aquired an old warehouse on the dock road, just by where the Irish fishing boats used to land, he was a frequent face watching live gigs around the city and allowed a few friends to rehearse in his little building.

"I used to just go by the building once a week and there would be a row of pound notes on the shelf. The bands just let themselves in and left their money, then it happened that there would be more money than i expected. More and more bands needed somewhere to practise. And thats how its began; i got a bigger building..."

"I used to just go by the building once a week and there would be a row of pound notes on the shelf. The bands just let themselves in and left their money, then it happened that there would be more money than i expected. More and more bands needed somewhere to practise. And thats how its began; i got a bigger building..."

With our own band rehearsing there, I was allowed the freedom of the building for these snaps. Whilst Vulcan Supplies full kits/amps, padded rooms and a full blown recording studio, as you can above, there are still some parts retaining original features such as the stone spiral staircase, the shuttered windows and hardwood fire doors.

.jpg)